on adrian chiles, obsessions and the fight for jazz(pt 1)

and lots of talk about furrowed brows.

(note - this is part 1 of 2 substacks this week.)

Given the nature of this Substack, you might be surprised to hear that presently, there is no other writer I see more of myself in than Adrian Chiles. Like many Brits, I’m aware of the broadcast work he does for basically every terrestrial TV station, but his bi-weekly column for the Guardian knows my mind.

The world often confounds him. He writes about things we don’t believe deserve air, let alone column inches. In his two write-ups a week, we learn closely about the goings on in his material life and how his brain navigates it.

need I say more

In a world where sub-editors impose salacious headlines on pieces to bludgeon readers into reading, Chiles’ grab your attention in their simplicity, often conjuring up an image of a man daydreaming or who has been taken in by an intrusive thought.

Orderly queues in pubs? They’re extremely civil - but need to end now, My adventures at sea have brought me many things. Mainly raw nipples and exhaustion, and I’d love to laugh like a baby again. But the best I can hope for is a big sneeze are a few of my favourites and in recent months, he’s delved into the deeper parts of his psyche.

You might think that his infamously furrowed brows complement the sourheadedness of these headlines. But I think it shows someone whose inquisitiveness is so entrenched that their face has permanently contoured to the expression of questioning. I also just think he has a physically heavy brow that’s hard to keep up.

I’m compelled to write about Adrian Chiles because, once again, he’s already spoken for me: “I may not understand jazz – but I know enough to know it’s wonderful.” He describes a show he went to:

The Fraser Smith Quartet were playing. The eponymous saxophonist – from Birmingham, as it happens – was accompanied by piano, double bass and drums. Disappointingly, but encouragingly too, I’m no longer the youngest in the room. Now I’m one of the oldest. It’s a mixed congregation. The relatively young are in attendance. Some of them really get it; others seem a bit bewildered to be there. I surmise a handful of couples are there on first dates.

On stage the musicianship is off the scale. Four players who I’d never heard of until that very day. Having tried, and failed, to learn the saxophone, I find every clean note that is blown miraculous, so I’m easily impressed. The double bass player is incredibly young-looking and prodigiously good. But his jacket is too big for him and I’m stressing that the sleeve is getting in the way. The drummer is much older – my age! – and I can’t take my eyes off him.

I had a similar experience when I went to see my very first jazz show, courtesy of the Tyshaun Sorey Trio at Kings Place last year. It was sold out and the crowd was different from the one Adrian saw: older, white, and chin-strokey with a smattering of young people, people of colour, and on dates like I was. Knowing nothing really about the genre, except watching documentaries about its major players, I was awestruck by the show but also got the sense that I was missing something. There’d be moments where, without notice in the middle of a tune, the crowd would start to cheer and clap. It became clear that the trio had deviated from Tyshaun’s music and had begun to perform jazz standards/well-known tunes. After the show, I discovered they were playing Wayne Shorter, Joseph Kosma, Ahmad Jamal, and Duke Ellington, and also that Tyshaun Sorey was kind of a big deal - a Pulitzer Prize-winning one at that. I had been in a sonic space that I loved but knew nothing about.

The Tyshaun Sorey Trio gig which was part of EFG Jazz Festival last year

I refuse to be a dilettante and this goes for everything in my life, not just the artsy stuff. People who are close to me often note how I have no cursory interests, only deep-seated ones that span many things from reality TV to different kinds of kitchenware to the Five Families and now I’ve added the weight of a hundred-year-old, deeply musically diverse genre to the rolodex. In my 32 years, I’ve not changed. I feel just like the 9-year-old girl who used to print out the lyrics of pop songs, alphabetise them by the artist’s last name, colour code them by gender and groups, put them in a binder, and bring them to school - where no one cared at all but I was happy. Then and now, I don’t like knowing things to impress or one-up people. I just like knowing things coz it’s fun.

Similar questions like the ones Adrian Chiles had flooded into me after the Sorey show:

How did these people get so good? Where do they live? How do they spend their daylight hours? What do they do when they’re not electrifying the air in basement jazz clubs?

Recently, it has started to keep me up at night.

I search furiously for information about the jazz artists that pop up in the articles and threads I look at, asking myself “What’s one more tab?”. I know Wikipedia hates to see me coming; a search about Max Roach becomes one about Duke Ellington, becomes another about Charlie Parker, about Ahmad Jamal, about Art Blakely, about Lee Morgan, about Bud Powell, about Wayne Shorter, about Stan Getz, about Eric Dolphy, about Horace Silver, about Abbie Lincoln, about Pharoah Sanders, about Alice Coltrane, about John Coltrane, Oscar Petersen, about Cannonball Adderely, about Davis, about Gillespie, about Hancock, about Monk, about Mingus (I’m on last name terms with them now).

I manage to somewhat casually bring up Bill Evans to some friends and tell them to watch Bill Evans: Time Remembered which I describe as something like “the best thing I’ve ever watched in my entire life”.

I decide to make a list that separates the best jazz artists by instruments - saxophonists, drummers, trumpeters, pianists, and clarinetists (my brother plays clarinet and I daydream about him forming his own trio). I google swing, bebop, hard bop, cool jazz, post-bop, modal jazz, jazz fusion, avant-garde jazz, free jazz - until I get fed up and think that it’s all nonsense. But then I get scared about not being able to know it all on my own and start googling Jazz history courses.

I pull from a Melodies and Masterpieces thread of the 25 most important jazz albums and place the vinyl records into my Amazon cart. Then I check the cart total and move them to my wishlist.

A year ago, when I was dabbling, I started Ken Burns' 1,140-minute opus Jazz. Now I come back to where I left off, more equipped to criticise it - stroking my chin, furrowing my brow like my hero, Adrian.

Friends fear she’s spiraling again…

When the idea of black radical came to me, I knew I wanted to investigate the genre as an absolute beginner, and I wanted readers to know I was just that. I’m not attempting to espouse new opinions, just - like everything I write about on here - things that I’ve discovered and find interesting. A simple person trying to make sense of an alive but ‘dead’ genre, a kind of Latin or ancient Greek.

It’s kind of an odd pick given that this Substack is billed as a Black alternative music newsletter. Blackness to jazz is like what is to hip-hop and I think that’s still known by anyone who has a personal or professional interest in the genre - or who has no interest in it too.

But like many elements of Black culture, it’s more complicated than that.

In minute whatever of Burns’ Jazz he states that by the end of WWII, tastes of Black people were slowly moving away from jazz to other genres like R&B and the initial incarnations of rock music - which would overtake jazz’s all-encompassing popularity by the 60s1. It seems to me that we haven’t looked back since, in so far as the genre’s commercial viability and Black mass interest.

This by no means means the genre is irrelevant to all Black people (read Substack 2 where I talk about how I’m not concerned with mass popularity) and its survival is valiant and deserving. Amongst other reasons, it’s been kept alive by its descendent, hip-hop and I like to remember that Nas’ father is the prolific jazz multi-instrumentalist Olu Dara.

I was really happy this tweet came across my feed because it’s pertinent. (checked through the thread and this is meant positively):

But Black people aren’t often in jazz audiences, neither does jazz feature consistently in Black magazines and media - this has been true for decades. Our absence causes serious problems. It erodes our sense of identity in the physical jazz space and has made room for white historians to get comfortable and ponder on their pages. One take that I recently read from a white writer is that the increasing output of avant-garde jazz in the 60s by the likes of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor alienated Black people because the sub-genre didn’t appeal to their…simple tastes? This is the kind of language that is used to separate the white high-brow tastes and the Black low. Even if this was the reason, it can’t be the only one.

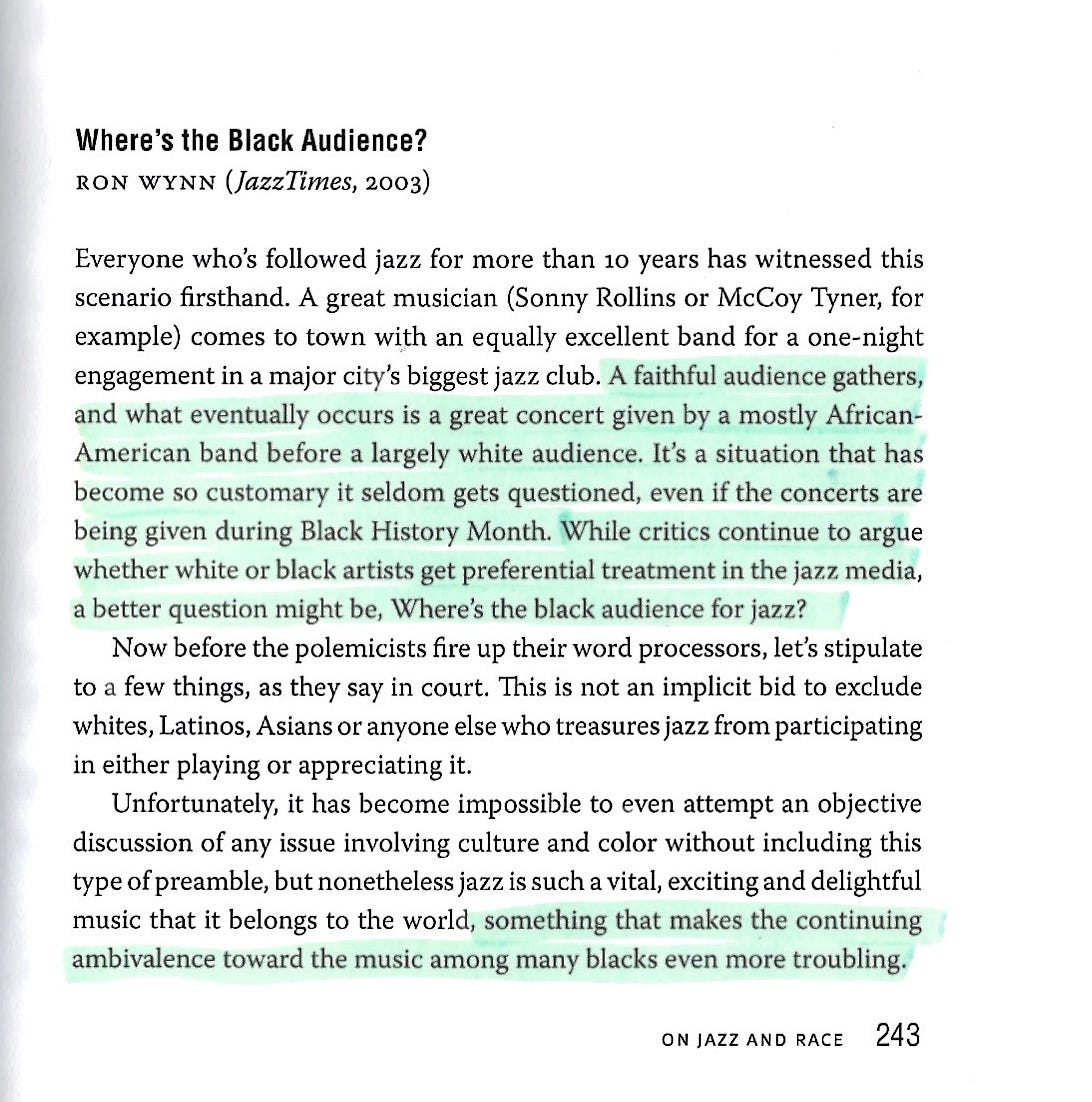

An outtake from Ron Wynn’s Where’s the Black Audience (2003):

In the full piece, Wynn bullet-points details ways to encourage more Black presence in jazz spaces:

1) More presence in African-American media, 2)A jazz equivalent of Vibe and The Source, 3) Less emphasis on history, hipness etc, 4)More publicity of online Jazz sites, 5) Jazz performances at venues other than those in white neighbourhoods, 6) Highlight young Black jazz stars.

Jazz criticism isn’t dead in mainstream papers, against all odds. Newspapers continue to cut column inches yet the jazz columns survive. Maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise; no demographic knows how to keep a job other than an old white man with white hair, respectfully, and so maybe it’s lucky that jazz criticism has been overwhelmingly white - back to when those old white writers were young white hipsters (probably and rightfully) obsessed with Charlie Parker.2

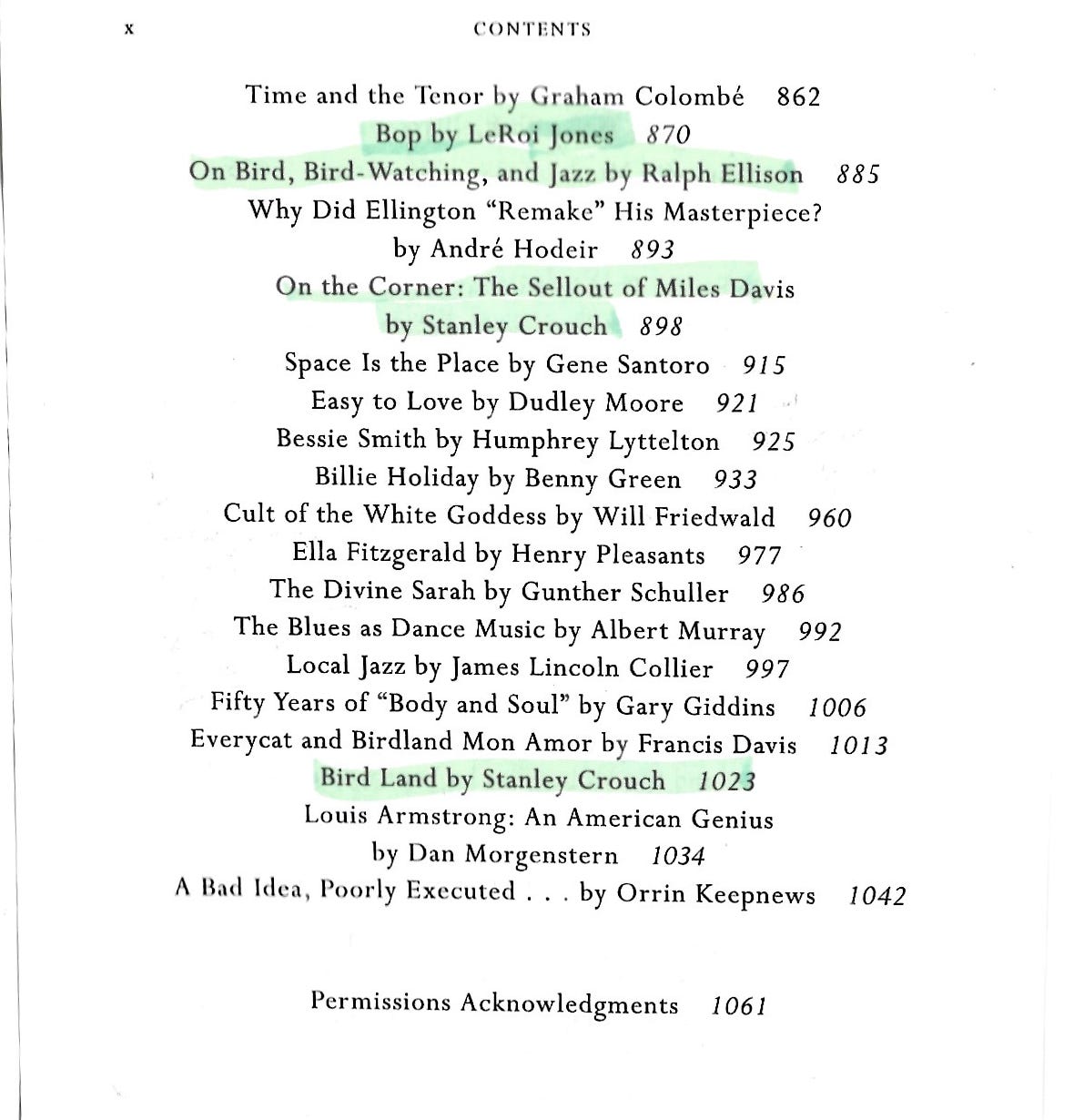

A couple of weeks ago I bought Reading Jazz: A Gathering Of Autobiography, Reportage and Criticism from 1919 to Now, (now being 1997) by Robert Gottlieb from a charity shop. At 1061 pages, it calls itself “the largest, most comprehensive, and most stimulating collection on jazz ever published”. Divided into three sections, Autobiography, Reportage, and Criticism - the latter two feature overwhelmingly feature words from white people, and if a follow-up edition of the book was written to include from 1997 to now, it would largely be the same.

Contents page from Reading Jazz.

Yes, I googled every single name. Some number crunching:

Of 88 articles on Reportage and Criticism, 8 of them are Black men, and 4 of them are white women.

Not pictured, but in the Autobiography sections, 22 of them are Black artists, 3 of them are white executives, and 8 are white musicians - 33 in total. Autobiography takes up just 325 pages of the 1061.

I bought Reading Jazz because I knew it would complement a book I bought a month before that purchase, Willard Jenkins’ 2022 book Ain’t But a Few Of Us: Black Music Writers Tell Their Story. The back cover reads:

Despite the fact that most of jazz’s major innovators and performers have been African-American, the overwhelming majority of jazz journalists, critics and authors have been and continue to be white men. No Major mainstream jazz publication has ever had a Black editor or publisher. Ain’t But a Few of Us presents over two dozen candid dialogues with Black jazz critics…they discuss obstacles to access for Black jazz journalists, outline how they contend with that world, and point out that these racial disparities are not just confined to jazz, but hamper their efforts at writing about other music genres as well.

In 2003, legendary Black jazz journalist Stanley Crouch wrote Putting the White Man in Charge:

I agree with his takes for the most part and his words echo those of his nemesis Amiri Baraka. I anticipated his comparison to rap music before I got to that part of the page and I think you’d be insane (which is fine) if you don’t see the parallels.

Last thought: I picked up these three issues of Jazz Journal from a second-hand bookshop. I’m yet to dig into them, but like a lot of Jazz photography - from cover art to press pics, the magazine covers are fucking cool.

White people also.

it’s probably important to note that just because jazz writing is all white, doesn’t mean it’s all bad.