black radical #1 black decelerent, black at glasto, brplaylist ft. bartees strange, tasha...

interviews, a playlist and some (un)fortunately candid, old festival photos.

interview: black decelerent

Khari Lukas (AKA Contour) and Omari Jazz - Black Decelerant - are musicians. The former releases music that’s a meld of the jazz, blues, and ambient traditions, padded with almost-sung, almost-spoken poems. Omari Jazz, too - 2020’s Dream Child is dream-like…if that is, your dreams include gentle beats and colour, intangible psychedelic swirls throughout. Their projects complement one another while maintaining a healthy creative distance that allows them singularity.

Their decision to collaborate was instinctual. “It was less of a decision, we’d known each other for ten years and had always talked about working together - in the earlier years we’d wanted to do an ambient project”... “We lost track of it for the better part of half a decade and then in 2020, Pedàl (the software) came out and it worked for us, as we could collaborate remotely”

What resulted is a sweeping but intimate body of work. In some respect it’s commanding - certain barbed tones and textures appear as though to shake us from our preconceived notions of what ambient music should be. But the album’s intimacy lies in how it sweeps into you and stays in your body, connected. You move with the music intuitively.

When engaging with Black Decelerent, viewing them as more multifaceted than the sonics is important. They occupy different spaces as well as music: visual art, journalism, poetry, and study - all of which inform the project. Underpinning their creative lives is an unencumbered occupation with what confounds and an interior preoccupation with its philosophical, epistemological, and sociological questions.

When Khari stumbled on Accelerationism1, a somewhat fringe philosophy that calls for drastic and intense capitalistic magnification, technological advancement, and all-out destabilising of social and political systems he knew he’d found something to sink his teeth into with Omari, a theory they could part contest and part harmonise with.

Here’s my (very) abridged, simple-minded, hopefully accurate explanation: Right-wing accelerationism, popularised by Nick Land, contends that to have radical social change, we must encourage capitalism to forge ahead as fast and as destructive as possible despite our casualty - “Nothing human makes it out of the near-future.” Left-wing accelerationism draws us back into the frame, arguing that capitalistic acceleration should be encouraged but guided to create the greater socialist good for human beings on the other side of it - “Nihilism without negativity”. Who or what that guide is the perennial question, closing with the idea that it could be a non-human subject.

What caught Khari’s attention was Aria Dean’s scholarship Notes on Blaccelleration where she dials back, reinstating that since “capital was kick-started by the rape of the African continent” through chattel slavery, Black people are otherwise non-human capital and subject simultaneously, existing at once and not in spite of one another - disrupting Land’s binary and timeline and arguing that ‘the guide’ that left accelerationism seeks is pre-existing racial capitalism.

Blaccelleration2 - a mating of Black radical thought and afro-futurism - places Black people at the centre of the apocalypse: accelerators who are subjects, “drawn to the end of the world” with vested interest to actualise a new world after the rubble.

Black Decelerent seeks to challenge the idea that intense effort and exertion are at odds with rest in Black and/or radical spaces and thought processes. “Part of it is about challenging the space that asks that you do more than your natural state and actively pushes you towards over-exertion or exhaustion, and all these late-stage capitalist ideas,” says Jazz.

Musically, Land and his comrades at the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit were obsessed with the prospect of Black British Jungle music as an exponent for acceleration: “Jungle functions as a particle accelerator, seismic bass frequencies engineering a cellular drone which immerses the body ... rewinds and reloads conventional time into silicon blips of speed ... It’s not just music. Jungle is the abstract diagram of planetary inhuman becoming.”

Yet, respectfully, Khari and Omari also question the idea that fast and intense sonic frequencies illustrate advancement. Equally, they challenge that slower, ambient music is an explicit invitation to physically slow down. “A lot is happening sonically on this album that isn’t analogous to what is stereotypically restful”

Interview below…

How did the themes of non-being, Blackness, and mourning come to influence the album?

Khari Lucas: We were both doing a lot of reading and consuming a lot of media at the same time. It was throughout making and listening to what we had made that themes emerged.

When did you come across Blacceleration?

Khari: It was in the middle of us making the record, that I came across Aria Dean’s Notes on Blaccelleration and I was immediately like, “This is it!”. Reading that was the first moment that we thought about an overall framework for the sounds we were making.

This article was my introduction to the concept of Accelerationism. I think it was serendipitous that my introduction to it was in its relation to Blackness and Black people occupying a foundational yet non-human position in capitalistic acceleration.

It also complemented the reading I was doing on Black studies in relation to consumption, film, and various art movements across regions and times. I saw [blaccelleration] as a thread that connects all of them in certain ways - as their foundation.

Black Deceleration pushed against the idea that the style of our music is presented as something to relax to. Well, we’re not perfectly pushing against this, but we’re framing it to be more purposeful and less about post-self-help, post-therapy, capitalist commodification of rest that markets and sells it as a need.

It's an interesting thing, you know, to touch on the need for space and rest, when we live in a system that denies us it unless this space and rest is something that can be sold.

But to discuss rest as radical through a racial lens…it’s an idea that’s more prevalent in the younger end of our generation. What Black radicals of the 70s and 80s seem to believe is the antithesis of this - that there isn’t time for rest at all.

Khari: It’s tricky for me because something I’m concerned with is dichotomy and multidimensionality in the way that we talk about these things. Part of the issue of commodification is that to sell something you have to flatten it into a digestible version of itself, and so you end up with conversations like posing the idea of the 70s revolutionary and like the modern person would be at odds [with rest] - I don’t think they have to be at odds.

And is rest a privilege only for the few?

Khari: Something that is also troubling monolithic ideas of rest as being literal material stillness. The monolithic definition creates a situation where the discussion becomes how only certain people can access it.

It’s rather asking: what are the elements that make something feel restful, nourishing and replenishing and what are things that you engage with that elicit those feelings that might not fit into the category of being literally still or relaxing?

Omari Jazz: The traditional definition of what we know as rest exists directly in tandem with capitalism, “you're resting from work, right?” I think this needs to be challenged and needs to be divested from capitalism.

I’m African, and my parents were economic immigrants to the UK. Their whole deal was to move here to give my siblings the best chance in education, social mobility, and careers. Their existence in this sense, is embedded in altruistic work. But what this means for their kids - and I see a lot of skits about African parenting along these lines - is that seeing you rest by watching TV or having a lie in, is terrible - there’s always something to be done.

Omari Jazz: That’s a really good point and interesting perspective and experience you have. From your parent’s angle, it’s “we’re taking a huge chance and we need to make good on every moment.” We also have different buttons to press in an emergency than white people…going back to your questions about who gets to rest. While the definition of radical rest can be true for all, it’s through a different lens and it’s more likely that rest is going to have more of a parasitic relationship for [Black people].

Khari: I’m also thinking about rest and acceleration. If the generation that preceded us came here to work for survival and the more work they did the better - which is its form of acceleration related to working - then it feels like our generation will be at the risk of the invert: “How much more can I be resting – more and more and more rest” What it is the end-point and what does that give way to?

What is the midpoint between these two positions?

Kkari: I think this is more of a personal philosophy and maybe even outside the concept of the record, but historically, and even people looking at their own lives and personal developments, you encounter a problem and you identify the cause of the problem, and the problem becomes The Great Evil and so you go all the way to the other side. But then you get a new problem because you went too far to the other side. Now you have to pull from something on the side you came from so that you get to the middle.

Everything is just that - being able to pump the breaks of the processing model. Rather than thinking of the Great Evil, we could think, “This is in excess right now of what it needs to be, but it couldn’t have got into excess if there wasn’t something valuable about it in the first place.

Finding a way to dial in the recipe so that these aren't conversations of totally through one thing out and then becoming 100% immersed in the other thing.

Spinning Blaccelleration on its head, how did you express the concept of Black Deceleration when making the record?

Omari: We didn’t shy away from different sonic modalities and moved through what people try to encounter when they’re listening through an ambient lens. So there’s tempo stuff on there, chippy, rugged, asynchronous shapes…we were conscious of contorting textures and shards and we weren’t afraid of movement.

As Khari said earlier, it’s not the physical act of rest that we’re trying to embody. It came in the form of being slow AND fast and more challenging rhythms and chops. And we’re showing up in spaces where I think we haven't typically been allowed to show up in, in a musical context, permanently. So we’re breaking through the novelty of that.

In the same notion of rest not necessarily sounding slow, though a lot of us think that that’s what it is and also leaning into the body and mind’s natural inclinations, is there a chance that we don’t know what rest sounds like?

Khari: Wanting to engage in an activity that's good for our body or mind, necessitates having a direct line to what your body and mind are feeling. But before you’ve developed this sense for yourself, you have ideas placed on you on what rest is meant to feel like. It takes having a realisation that you can break down these ideas to what the right ones are for you. I’d argue that many people don’t know.

True, I think this is more often the case…in my circles at least.

Khari: I’m also thinking about language and our current endeavour in trying to articulate what this ‘Thing’ is and what it could sound like. I think language can become an obstacle in trying to feel and figure out what’s internally embodied. These can be feelings that you objectively recognise are there but once we try and make other people understand it, we might be losing something…

I hear musicians say how, once they’ve released their music, it’s no longer theirs. Do you surrender to the subjectivity of your work?

Omari Jazz: It’s interesting…I think this music is an intangible force and another form of non-verbal communication that is as close to the feeling being felt as can be. It either resonates with you in a way that’s asynchronous to the original concept or ideas of rest for you.

Khari: I'm typically not so interested in my work being understood…I think it’s kind of a fool’s errand. If somebody encounters my work, and they get something out of it - emotional, practical, or functional, then it’s been successful even if it does not perfectly sync up with my set of thoughts. It doesn’t mean there’s been a failure in the communication of the idea.

What is your intent for the album and what has it meant to you?

Omari: Acceleration and then ultimately our Black Deceleration was so baked into the process that it didn’t feel like we were creating this externalised event. We were holding this framework and this body of music just to ourselves. It was so much of a journey for me and Kkari, exploring these ideas and these sounds back and forth. In the course of making the music, we didn't really exchange words or say “Why don’t you put this here, or that there”, it was very much in the tradition of jazz and experimentation and a lot of trust.

Khari: One thing we joked about was that above all - when I try to sum up our desire for the record was that we didn’t want it put up on any white yoga studio playlist (laughs).

That would be very tragic, hopefully, that doesn’t happen.

interview: black at glasto

Laying on my sofa, not having moved for over an hour, I was mostly content with not going to Glastonbury this year, pretty happy with this vision of laziness I’d put myself in. Trawling through Instagram, I awoke from my partial slumber when I noticed a Black peer of mine who was in attendance tag a page called @blackatglasto. It’s a page dedicated to showcasing Black presence at the famed festival, whether they’re punters, performers, or workers.

Here’s a photo of a completely sober me and Michael Eavis. NYC Downlow, I think.

I wouldn’t necessarily say that people looked at me strangely when I said that I’ve been before, but since it’s mostly associated with indie/alternative rock music - this is changing - I sometimes sensed subtle surprise that I’d be interested. On the other hand, Black people - especially my mum - were more critical of the fact that I was opting to camp, doing away with the modern conveniences of contemporary life and access to bog standard hygiene.

Extolling the virtues of safe sex with condoms that someone has dropped, near the Park Stage if my memory serves. As I write this I’m thinking about that person’s unplanned child, who is now eight years old.

Before we bore our souls watching Solange on West Holts Stage

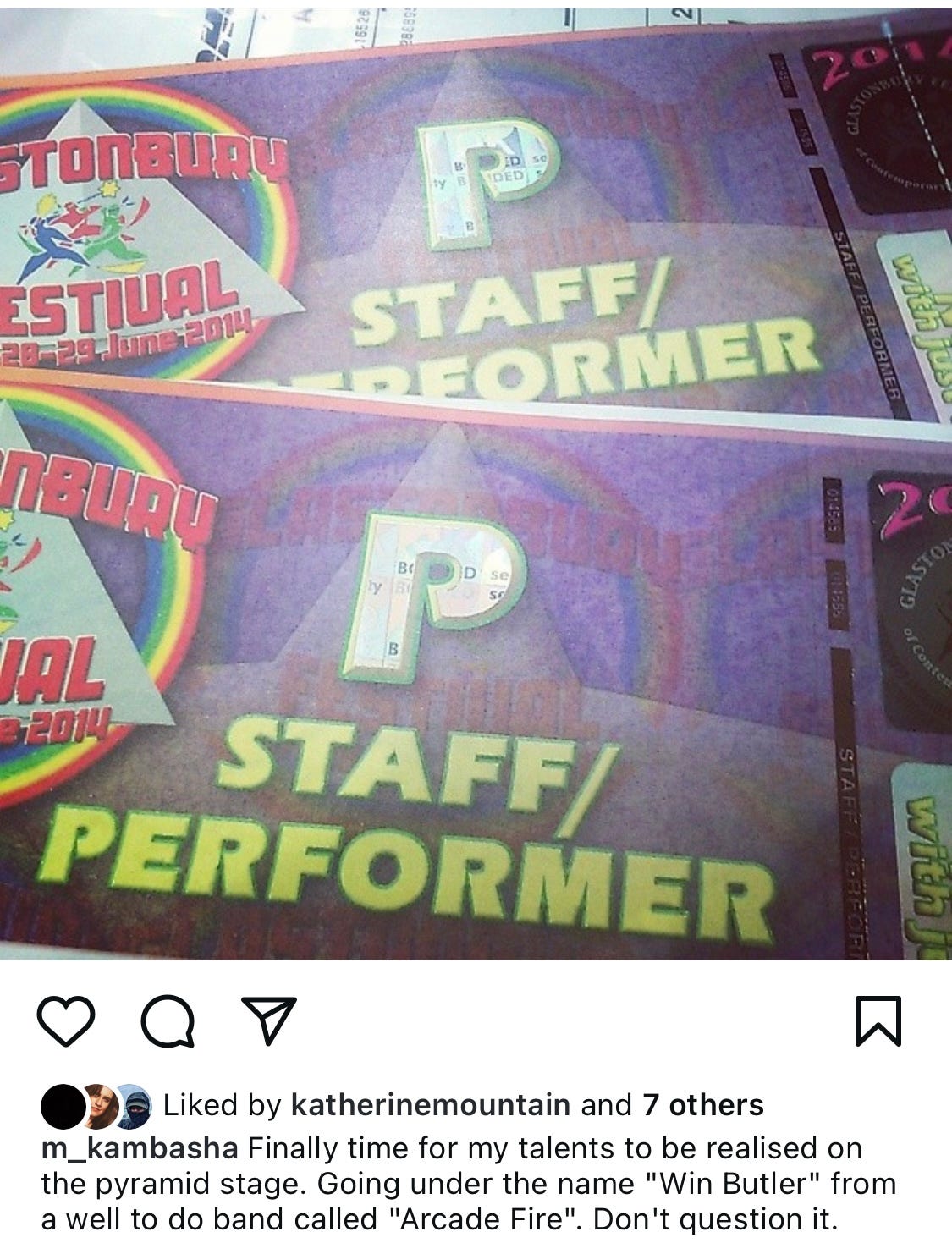

A 2014 humble brag post with a total of 8 (eight) likes

But I’ve been three times and I’ve loved every single one, despite emerging from it barely alive, broken and penniless. I loved the idea that there was this initiative that was highlighting Black presence in this space.3 I’ve had such magical times there and I think Black at Glasto could do amazing things by encouraging more of us to go, and further diversifying festival spaces. Below is my chat with Elsie, one of the founders.

Where did the idea of Black at Glasto come from?

I’ve been attending Glastonbury for the last 10 years, since I was 18, usually in a working capacity, as a stage artist liaison. For the first few years, I always attended alone.

I’m quite comfortable being alone and I had to be in some respects. However, when I had the pleasure of being assigned to a stage run by a predominantly black stage production team, managing predominantly black African/Caribbean artists, I immediately felt safe and at home. I remember my first Glastonbury distinctly, it was when I first properly connected with Afronaut Zu, Sophia Thakur, and Chantal Azari.

@blackatglasto Instagram

We were practically all attending the festival by ourselves however, somehow by divine fate and intervention we became unbreakably connected and instantly formed such a magical group, which completely changed the trajectory of my festival experience.

Every year since, I always experience that initial feeling of loneliness and othering, which completely vanishes when I meet other people from a similar background to me. Working backstage I also always see other black/mixed artists who you can just tell look physically uncomfortable and perhaps feel out of place.

Black at Glasto was created really to help reduce those feelings of loneliness and create a safety net of community and connection for anyone who wants and needs it out in the fields.

Above other festivals, why did Glastonbury feel like the perfect festival to fulfill the concept?

I fell in love with Glastonbury the first time I went. From walking through the Healing Fields to discovering incredible new artists, Glastonbury is genuinely magical - I attribute some of my memories to those fields.

I’ve been asked if I’d expand Black at Glasto to other festivals, but I don’t think I would. I’m not trying to create a monopoly or capitalise on the Black experience and our need for community. I think it’s more important for people who live and breathe in different spaces and festivals to create similar initiatives and communities for themselves and in their authentic way.

Black people have always been present in festival spaces, but when we’re the majority in them, they’re often criminalised, i.e. Notting Hill Carnival as depicted in media and the now abolished Form 696. Black at Glasto seems like a radical need.

While I think taking up space at Glastonbury is radical, I think festivals like City Splash, which is Black-owned, are even more radical. We also have quite a lot of Black interest festivals like Afropunk, Afronation, and Afro Futures. I wonder how we’re documenting and broadcasting these festivals can help amplify our culture.

The other thing is that a lot of us from first-generation Black households, don’t like the idea of spending numerous days in tents with limited access to showers, running water for hygiene upkeep, and having holes in grounds for toilets.

I’d love to see an organisation creates festivals that combine the ethos of Black interest and camping culture: an Afro-Caribbean camping festival with proper accommodation, cute toilets, adequate sanitary facilities, and completely immersed in our culture.

As Black people we often don’t align ourselves with festival culture - we buy into the predominating myth that they are for white people. Are initiatives like yours important in helping us re-imagine our associations with these spaces?

This year we received a lot of feedback from black people who didn’t attend Glastonbury saying that our content and community helped them consider attending next year. Many said they didn’t think ‘Glastonbury was for us’, but in seeing us take up space, they felt more encouraged and interested in attending.

That aside, at Glastonbury we’re seeing more cultures take up space, from Glasto Latino which is a tent dedicated to Latin American music, to the latest addition of “Arrivals”, which is a space dedicated to South Asian Culture. It’s only natural that a space for African/Caribbean cultures to also follow suit.

What were the vibes like on the ground?

Honestly, the vibes on the ground were amazing. We made a Black at Glasto group chat community and there were a lot of artists in it who took the opportunity to plug their performances - most of us tried to attend each other's set where possible. After their sets, the chat would be flooded with compliments, videos, and pictures. It was really wholesome!!

What artists did you go and see?

Tems, Burna Boy, Cyndi Lauper, Shania Twain, Ragz Originale, Silhouettes Project, Sambee, Caxxianne, Charisse C, Mercedes Benson, Caleb Kunle, and soooo many more! It was awesome.

Any other comments?

Just stay tuned! Follow us on Instagram @blackatglasto_ and keep us in your prayers!

I understand the value, importance, and also the responsibility of creating a space and an initiative like this, and I do hope to do it and everyone justice. If you want to help, support, or get involved please reach out - info@ourpeoples.co.uk

If you know Emily Eavis please also plug us! We’d love to officially collaborate with the Glasto team!

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/11/accelerationism-how-a-fringe-philosophy-predicted-the-future-we-live-in

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/87/169402/notes-on-blacceleration/

https://www.theguardian.com/music/article/2024/jul/03/black-joy-at-glastonbury-photo-essay